The NATO STO SAS-161 Research Task Group (RTG) – Military Aspects of Countering Hybrid Warfare: Experiences, Lessons, Best Practices Volume V: Military Implications

Published: 10/18/2023

Author(s) : Multiple

STO PublicationType: Technical Report RDP

Publication Reference: STO-TR-SAS-161-VOL-V

DOI: 10.14339/STO-TR-SAS-161-VOL-V

ISBN 978-92-837-2488-9

STO Publisher STO

Access: Open Access

Executive Summary

The NATO STO SAS-161 Research Task Group (RTG) investigating “Military Aspects of Countering Hybrid Warfare: Experiences, Lessons, Best Practices” is meant to inform the full spectrum of military planning at the Alliance and national level. This functionally oriented analysis touches all aspects of military effectiveness and help inform our collective efforts to account for the challenges of contemporary, and expected future characteristics of competition, conflict, warfare, and warfighting.

With a focus on contributing to the long-term military effectiveness of the Alliance, Ukraine, and the individual Ally and Partner nations, the RTG applied the fundamentals of net assessment in developing two distinct research streams. Both research streams study contemporary Russian behaviors related to competition, conflict, warfare, and warfighting. The first stream further investigates, from Ukraine’s perspective, Russian aggression against Ukraine and Ukrainian institutional responses and preparations up to the full-scale invasion by Russia on 24 February 2022. The second research stream, undertaken by the non-Ukrainian members of the RTG, develops national or mission-specific case studies investigating Russian behaviors within differing contexts. The intent of this second stream is to identify military-specific aspects of those behaviors. The analysis and deductions related to each research stream are then combined and distilled into military implications in this, the final and summary volume of SAS-161 reporting.

The research and analysis of the RTG uncovers several overarching conclusions. First, Ukraine provides an exemplar of military effectiveness grounded upon superb military adaptation and flexibility. The current effectiveness of Ukraine’s armed forces is rooted in almost 9 years of effort to modernize and transform Ukraine’s conceptions of security and defence. As with any situation, there is an historical and contemporary context that must be appreciated and taken into account but there is much to learn from Ukraine’s actions.

Second, it is imperative that each threat is studied in a way that respects the context of adversary decision making and the specifics of threat behaviors applied to each target. Conversely, each target of Russian malevolence must be studied to understand the historic and contemporary conditions that create both vulnerabilities and shields against the Russian threat. When faced with multiple threats, each must be understood individually before designing comprehensive responses. In other words, a net assessment mindset applied to threat-based planning will result in greater understanding of threat, strengths,

vulnerabilities, and risk.

Third, at the national level, the concept of “total” or “comprehensive” defence (e.g., the idea that national security and defence must be seen as a whole-of-government and whole-of-civil society responsibility) is the root foundation of military effectiveness. Such conceptions of national defence help clarify the role of military forces in relation to other instruments of national power, thereby contributing to the political effectiveness and the reduction of friction between bureaucratic

organizations. These robust national conditions, in turn, strengthen the effectiveness and cohesion of Alliance or coalition military effectiveness.

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Military Effectiveness

The NATO STO SAS-161 Research Task Group (RTG) investigating “Military Aspects of Countering Hybrid Warfare: Experiences, Lessons, Best Practices” is meant to inform the full spectrum of military planning at the Alliance and national level. The functionally oriented analysis and the country-specific case studies developed by the RTG touch all aspects of military effectiveness and help inform our collective efforts to account for the challenges of contemporary, and expected future characteristics, of competition, conflict, warfare, and warfighting.

Defence scientific research and development activities must, in the first instance, seek to contribute to the military effectiveness of the forces they support. Military effectiveness is defined as:

the proficiency with which armed forces convert resources into fighting power. A fully effective military is one that generates maximum combat power from the resources physically and politically available to it. The most important attribute of military effectiveness is the ability to adapt to the actual conditions of combat and conflict (vice those that were assumed would occur). Military effectiveness is comparative and can only be assessed against a likely opponent or a rigorous composite adversary through a pacing threats construct.1

Military effectiveness has political, military-strategic, operational, and tactical level components and is inextricably tied to military learning, adaptation, and innovation.2 As might be expected, military effectiveness is defined differently depending on the purpose of the individual scholar. While we ascribe to Williamson Murray and Alan Millett’s national and organizationally-focused construct, others have focused on the ability of military formations to generate, apply, and reconstitute combat power [6]. Still others apply notions of effectiveness at what we might call the service or environmental level (e.g., Army, Navy, Airforce, etc.) [7], [8]. Scholars have also applied Murray and Millett’s framework to assess gaps in tactical level military effectiveness as a means of correcting national level political, social, and military historiography [9]. Of greater, more recent frequency, many have built upon Murray and Millett and their individual and combined work investigating learning, adaptation, and military innovation to focus on the specifics of the intersection of technology, doctrine, organizational culture, and other factors, and the implications for military effectiveness in contemporary times [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. Regardless of the particular focus, all of these consider political (inclusive of socio-cultural, economic, and other national factors), military-strategic, operational, and tactical issues affecting the ability of the armed forces to achieve desired ends.

Notions of military effectiveness color the work of many scholars in several fields of study, even if the words “military effectiveness” are not explicitly used. Moreover, the use of the words “military effectiveness” by authors certainly predates the work of Murray and Millett but their framework has proven sufficiently resilient to stand the test of time and, even if used as a foil, the phrase has been employed in multiple academic fields of study.3 It is for this reason that we loosely apply the military effectiveness framework as a guide for the work of SAS-161. The framework is relatable to a substantial body of serious academic and professional literature, it provides an innate flexibility that enables the integration of a broad range of subjects and helps focus our analysis for a particular purpose ‒ the provision of STO support to the NATO military instrument of power.

1.2 Background

The SAS-161 RTG is the second Systems and Analysis Studies (SAS) activity conducted in collaboration with Ukraine. During the period 2015 ‒ 2017, the SAS-121 Research Specialist Team (RST) investigated in detail the Russian annexation of Crimea and the instigation of its campaign in Eastern Ukraine.4 That collaborative research activity demonstrated the earnest, forthright desire of our Ukrainian partners to investigate Russian methods of conflict, warfare, and warfighting, share their experiences, and work closely with NATO. The intent of SAS-121 was to contribute to the study and learning of contemporary conflict and warfare to help collective efforts to address shared security and defence challenges.

SAS-161 follows in the path of SAS-121 by studying the military aspects of countering hybrid warfare to better understand individual and collective experiences, develop and share lessons, and identify best practice.

This present work partnered the National Defence University of Ukraine (NDUU) with analysts from Canada, Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Finland, Great Britain, Latvia, and Sweden, and NATO SOF HQ (NSHQ) via the SAS Panel and the STO Collaboration Support Office (CSO). The work was Co-Chaired by Canada and the NDUU. At the NDUU, the “Project Kalmius” team was led by the Ukrainian Co-Chair of SAS-161, Colonel Viacheslav Semenenko.

Our work has two distinct research streams, both focused on studying Russian behaviors related to competition, conflict, warfare, and warfighting. The first stream further investigates, from Ukraine’s perspective, Russian aggression against Ukraine and Ukrainian institutional responses and preparations up to the full-scale invasion by Russia in February 2022. The second research stream was undertaken by the non-Ukrainian members of the RTG and sees the development of national or mission-specific case studies investigating Russian behaviors in specific differing contexts. The intent of this second stream is to identify military-specific aspects and implications of that behavior.

1.3 Method

Designed and approved in October 2019, the SAS-161 work program seeks to provide a unique contribution to the broader literature on “hybrid” or contemporary warfare by best exploiting the talents of, and the information available to, the RTG members, all of whom are involved in defence planning or professional military education systems at the national or Alliance level. In an effort to differentiate from some other portions of the very large, and growing, body of literature on hybrid warfare, the RTG work program was designed to adhere to the fundamentals of “net assessment” while striving to produce analysis focused on the aforementioned conception of military effectiveness.

Net assessment is the comparative analysis of military, technological, political, economic, and other factors governing the relative military capability of nations.5 Its purpose is to identify problems and opportunities that deserve the attention of senior defence officials [19], p.9. Net assessment is a practice that applies distinctive perspectives to identify problems, including organizational and socio-bureaucratic behavior within specific contexts, as a means of determining meaningful balance of force estimates and plausible strategic interactions to inform decision making (adapted from Ref. [20]). A Net Assessment mindset works to strengthen critical thinking while countering received wisdom or group think and is most valuable where it fosters the provision of contested advice to decision-makers. Most importantly, a net assessment mindset demands the study of ourselves and our adversaries both.

For military planning purposes, net assessment is focused on power relationships: it is a means of capturing and orienting decision-makers to the exploration of strategic interactions ‒ in all their complexity and variables ‒ between and among actors in the operating environment as a way to expose gaps and opportunities. This allows analysts to better understand contexts and what constitutes relevant change in the strategic environment that affects military decision making.6 As analysts, it also allows us, in fact forces us, to characterize the bounds of competitive military space. In support of an estimative process, net assessment frames military problems as strategic interactions as a way to think about choices and their impacts [23]. And it forces us to contain our analysis within the boundaries or parameters of a particular time period.

In this way, net assessment is an approach ‒ a way of thinking ‒ that incorporates all-source and inter-disciplinary material and recognizes the intellectual necessity of both nurturing and managing contested advice at an organizational level. Net assessment, therefore, is not only, potentially, a “capacity” or a “capability” as it has been recently described in various restricted distribution Alliance documentation.7 As such, it is not surprising that organizations deal with it hesitantly, certain that it might be necessary, but uncertain as to how or why. For instance, the 2010 NATO Strategic Concept calls on the Alliance to ensure it is “at the front edge in assessing the security impact of emerging technologies, and that military planning takes the potential threats into account.” Such admonition calls out for comparative assessment in aid of pursuing the strategic objective of maintaining competitive advantage over potential adversaries ‒ but of course does not explicitly refer to “net assessment” [24], p.17. Neither, then, is it surprising that net assessment is variously considered to be a product, a capability, a process, an intellectual construct and a methodology. Nonetheless, both analysts and practitioners should embrace net assessment as anorganizational mindset or approach that works to strengthen critical thinking while countering received wisdom or “group think,” rather than pursue it as an “authoritative” singular endeavor or point of departure for planning.8

With this in mind, the SAS-161 work program is guided by relatively straightforward parameters comprised of three pillars.

The first pillar is the focus on the military aspects of contemporary competition, conflict, warfare, and warfighting. While political, economic, financial, and other factors are relevant to some of the individual studies comprising the SAS-161 body of work, those non-military factors are only considered insofar as required to understand their military implications within the context of a particular case study.

This focus does not disregard the interplay between the military and other instruments of power; rather, we apply this focus to help identify gaps in military authorities, responsibilities, legal frameworks, and policy that are exposed during the research and analysis. This is critical as the SAS-161 work is conducted under the auspices of the Alliance’s Science and Technology Organization (STO) and therefore must contribute to the use, development of, and effectiveness of the military instrument of power.

The second pillar is that Russia, inclusive of proxies and others that might contribute to Russian goals, is the sole threat actor under consideration. While other threat actors might apply methods similar to those of Russia, adherence to the principles of net assessment means that each threat actor (and target ‒ e.g., Ukraine or any of the states considered in our case studies) must be considered in their own context. Broadening the research and analysis to include other threat actors risks studying the methods rather than the actor ‒ something that is arguably of limited utility for military planning purposes and, regardless, has been done by many others.9

The third and final pillar is the preference for contemporary primary source material in the research and analysis. As much as possible given the intent to work at the unclassified level, the members of the RTG employ original official documentation, interviews, and other similar material considered to be primary source.

This requirement is meant to emphasize and exploit the specialized knowledge and perspective held by the RTG members and thereby distinguish it from analysis conducted by those outside of defence institutions.

No single project can be comprehensive and SAS-161 is no exception to this rule. For example, there is limited detailed discussion of the use of space or cyber capabilities and the case studies are not intended to span all recent targets of Russian malevolence or those countries that fall within Russia’s self-proclaimed sphere of interest. Nonetheless, our research and analysis contribute to the broader body of work on contemporary competition, conflict, and warfare and contribute to the effort to better understand ourselves and Russia as an adversary.

With these parameters, the case studies and the Ukrainian Project Kalmius research and analysis were developed independently under central direction and guidance from the Co-Chairs. This approach maximized the disparate professional and educational backgrounds and perspectives of the RTG members. The implications development process described in the “Military Implications” volume of our reporting was then used to distil the military implications from the collated main analytic deductions identified in each individual piece of work. Military implications are defined as:

The implied consequences of credible deductions arrived at through the application of professional judgment. An implication should be actionable, without identifying courses of action, and relate to one or more capability components or enablers in order to inform military planning. For operational research and analysis, any implication is likely to affect multiple functional areas, can identify new requirements, validate current capability paths, or suggest capabilities of declining relevance. Implications must centre upon military effectiveness and credibility. (Adapted from Ref. [28]).

The implications development process allows for the identification of commonalities and contrasts across all of the main deductions, enabling the integration of the entire body of RTG scholarship into a whole.10 The incorporation of an implications development process as a core portion of the work program reinforces our focus on the military aspects of hybrid approaches and the application of such methods by a specific threat actor (Russia). The result is a specific set of recommendations tailored to planning functions. Consequently, we remain within the scope and intent of the NATO STO SAS mandate, respectful of the role and authorities of those executing planning functions in NATO and national level headquarters and remain true to the framework of academic and professional literature on military effectiveness and net assessment that provided the intellectual guidance in the development of the RTG work program.

1.4 Overview of Analysis

The specific topics covered in this volume of SAS-161 reporting are detailed in the next section. Overall, however, there are some major deductions resulting from the work as a whole.

Ukraine provides an exemplar of military effectiveness grounded upon superb military adaptation and flexibility. The current effectiveness of Ukraine’s armed forces is rooted in almost 9 years of work that has modernized and transformed Ukraine’s conceptions of security and defence with the support of a wide variety of international partners. As with any situation, there is an historical and contemporary context that must be appreciated and accounted for but all those interested in security and defence affairs will do well to study Ukraine’s actions to glean insight and lessons.

The reporting confirms the imperative to study each threat in a way that respects the context of adversary decision making and the specifics of behaviors directed at each target. Conversely, each target of Russian malevolence must be studied to understand the historic and contemporary conditions that create both vulnerabilities and shields against the Russian threat. Even when faced with multiple threats it is important that each is understood individually before designing comprehensive responses. In other words, a net assessment mindset applied to threat-based planning will result in greater understanding of threat, strengths, vulnerabilities, and risk.

Our analysis helps to highlight that, at the national level, the concept of “total defence” or “comprehensive defence” (e.g., the idea that national security and defence must be seen as a whole-of-government and whole-of-civil society responsibility) is the foundation of military effectiveness, at least from a homeland defence perspective. This is because such conceptions of national defence help clarify the role of military forces in relation to other instruments of national power and, hopefully, contribute to high levels of military political effectiveness.11

Finally, despite the fact that much of the work of the SAS-161 RTG was conducted remotely, in a distributed fashion, first because of the pandemic and latterly because of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, collaborative projects such as this contribute to our ability to reach greater levels of understanding and improve our knowledge on contemporary security and defence challenges.

1.5 Topics Covered in this Volume

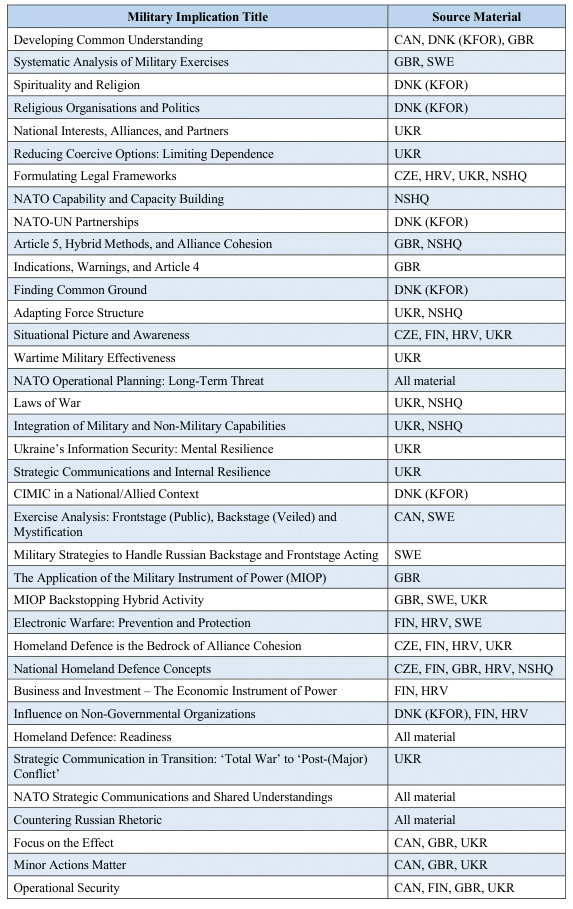

This volume of reporting from SAS-161 covers the military implications developed by the RTG based upon all material developed as part of our work. The section following this introduction describes the purpose, intent, and method of the military implication development. That section is, in turn, followed by the implications. This volume also contains two annexes. The first links source material to each implication. The second details a range of topics suitable for further collaborative research analysis with Ukraine. These topics were developed by the RTG in March 2023. Also included in this volume is the glossary employed by SAS-161.

2.0 MILITARY IMPLICATIONS DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK

2.1 Background

Typically, analysis of the sort that occurs within defence organizations, including NATO, provides deductions, recommendations, or both at the conclusion of an activity. Neither deductions nor recommendations are implications, even when considering common dictionary definitions. Implications are the middle ground between expert analysis and direction and are critical to providing decision-makers with context-relevant information that is comprised of both evidence and professional judgment. For STO activities the mandate is to support Alliance military activities rather than direct change. Concluding analysis with deductions may be considered sufficient but applying professional judgment to enhance what those deductions imply for the consumer of our work not only helps to stimulate thinking about what can be done about problems or opportunities but also, because of access to privileged information, distinguishes our work from that of academia and others outside of the Alliance structure. Most importantly, for collaborative group work such as that of the SAS-161 RTG, working towards the development of implications helps transform the work from that of individuals to that of the collective by applying the professional judgment of the whole.

SAS-161 is the second NATO STO SAS research activity conducted in partnership with Ukraine. It follows SAS-121, the first collaborative partnership, and SAS-127, which explored the NATO-specific implications of the SAS-121 RTG analysis. The SAS-127 work applied an informal structure to organize the development of implications but did not adhere closely to language befitting the middle ground between scientific deduction and direction. This resulted in the development of “implications and recommendations” and much use of the word “should.” In retrospect, the work would have been strengthened by a greater “if – then” emphasis, meaning, a more direct link to consequences. One of the goals for SAS-161 is to improve upon that earlier work by applying a somewhat more formal approach to develop implications for NATO, Ukraine, NSHQ, and individual countries, in that order of priority.

By working to both create and apply a NATO-specific implications development framework, SAS-161 will be contributing to the methodological improvement of SAS activities. An initial framework comprised of policy, process, military (operational), education, interagency, doctrinal, and research and development categories will be applied and refined in the course of the RTG work program.

2.2 The Idea of Implications

Military implications are the implied consequences of credible deductions arrived at through the application of professional judgment. An implication should be actionable, without identifying courses of action, and relate to one or more capability components or enablers in order to inform military planning. For operational research and analysis, any implication is likely to affect multiple functional areas, can identify new requirements, validate current capability paths, or suggest capabilities of declining relevance.

Implications must center upon military effectiveness and credibility (adapted from Chuka et al. [28]).

Military effectiveness is defined as the proficiency with which the armed forces convert resources into fighting power. A fully effective military is one that generates maximum combat power from the resources physically and politically available to it. The most important attribute of military effectiveness is the ability to adapt to the actual conditions of combat and conflict (vice those that were assumed would occur). Military effectiveness is comparative and can only be assessed against a likely opponent or a rigorous composite adversary through a pacing threats construct.12 These terms and their definitions, are equally applicable to NATO and national militaries.

Working toward the development of military implications is most important during collaborative group work. In such environments the use of a framework will help the group lead or facilitator to transition the work of individuals to that of the collective, compel the group to remain true to the evidence, tease out and properly account for dissenting and opposing views, challenge biases, and avoid the understandable temptation to seek consensus. In an Alliance context, this is particularly important as there is a natural tendency, or indeed a requirement, to strive for agreement across all Allies. For scientific activities, there is a balance to be struck. In developing the military implications of scientific analysis, we must try to come to some agreement on the consequences of the evidence but this must not be purchased at the cost of discounting or ignoring the evidence. A lack of consensus on the consequences of the analysis does not indicate failure; such disagreement should be expected and can be important for the identification of areas requiring additional research and analysis. In sum, a structured, bounded approach to thinking about the military implications or our work improves the defensibility of the analytic inputs to the development of military advice.

2.3 The Implications Development Framework

Thinking about implications requires thinking about context and applying our deductions against that context. Put differently, an implications development framework must be tailored to the organization being supported by the research and analysis – most specifically the authorities, responsibility, and lines of business (planning). Implications may affect more than one mandate within current organizational structure. Consequently, implications should not necessarily be tailored to contemporary structure.

Military organizations operate within tightly arranged planning environments that consider different time “horizons” that comprise the continuum of planning. The variety of planning activities that occur require consideration of, or are influenced by, internal and external drivers. Internally, the expectations of political and military authorities create what might be called “strategic guidance.” Strategic guidance will include formal and informal policy, political and military direction and guidance, mission, output, task, and force posture direction and considerations, and for many Western-oriented countries, formal and informal expectations of allies and partners. The external component is largely comprised of threat-based considerations that form the bulk of contemporary or future operating environment assessments or estimates, including the strategies, stratagems, and doctrines of the adversary. The external component must also consider the geography (and the natural environment related to geography) in relation to areas of operation and “blue” thinking on warfare and warfighting.

The military planning environment will have near and long-term components. The near-term component is typically in relationship to the authorities and responsibilities of operational or combatant commands and immediate-term political considerations. The long-term planning component is normally associated with force development and design.

While it is important to have reference documentation associated with, in particular, the strategic guidance when building an implications development framework, it is more important that the participants in the work are familiar with the documentation and current decision-making context and have professional backgrounds appropriate to the subjects being discussed. Put differently, the development of implications involves the application of professional judgment. Consequently, success in this endeavor hinges upon engaging people with sufficient professional experience, subject matter knowledge and expertise, and a mindset attuned to the application of their scientific work to actual military problems. What might be considered “sufficient” in terms of knowledge and expertise will be contingent upon the context of the work. Ideally, deliberations can take place at the classified level as it is within these secure confines that the most sensitive topics and considerations can be raised and debated and these are the levels that enable the most detailed discussions to occur. The major difference between classified and unclassified work is the specificity allowed by reference to documentation that highlights discrete aspects of the problems being considered by the consumers of our work. However, meaningful implications can result from unclassified discussions and, in fact, wording can be employed that will speak to those working within classified military planning spaces.

SAS-161 is bound to the NATO Unclassified, releasable to AUS, CHE, IRL, JPN, SWE, UKR level of classification. This limits the ability to openly consider, and make reference to, most NATO documentation that might inform the RTG deliberations. Consequently, the initial SAS-161 implication development framework will use categories similar to those used in SAS-127: policy, process, military (operational), education, interagency, doctrinal, and research and development.

2.4 Application of the Framework

SAS-161 must consider, in the first instance, the implications of our analysis for NATO military planning.

For NATO, the near-term time horizon is associated with SACEUR and the long-term with SACT. The Military Committee binds these “Bi-Strategic Commands” (Bi-SC) and develops military advice to the NATO political level.

Along with planning timeframes, we must also consider current military authorities and responsibilities. It is all too easy to simply advocate for expanded military authorities to counter the methods of our adversaries. Doing so, however, risks the increased militarization of non-military problems, implies military responsibility for broader security issues, and carries with it the potential for undermining the legal, regulatory, and culturally (organizational and otherwise) based system of checks and balances that should be seen as a strength of liberal democracies. It should require a truly exceptional circumstance to make an argument for expanded military authorities. In addition, all Alliance activities are highly structured, agreed upon, and the most significant activities are modified only after considerable discussion and effort. Any implications suggesting a modification of military authorities must consider the bureaucratic difficulty of addressing an implication ‒ anything that reads as being too difficult may simply be disregarded. In such cases, incremental change may be preferable to no change.

The following section provides the implications developed by the SAS-161 RTG.

3.0 SAS-161 MILITARY IMPLICATIONS

3.1 Introduction

Using the basic framework described in Section 2.0, the SAS-161 RTG developed the following military implications through assessment of all of the research and analysis conducted by the team. The implications are relevant to all levels of military planning with a focus specific to NATO, Ukraine, or individual nations.

In many cases, an implication is relevant to all three. The ordering of the implications is not hierarchical and the categorization resulted from the collation of refined draft implications. Those refined drafts were further distilled into the material presented here. The categories of the implications are: Net Assessment – Understanding, Policy, Military Instrument of Power, Homeland, and Information Environment. The implications below imply a program of research and analysis that could be pursued at the Alliance or national level or, in many cases, collaboratively with Ukraine.

3.2 Military Implications

3.2.1 Net Assessment – Understanding

3.2.1.1 Developing Common Understanding

Deduction

Alliance cohesion must never be taken for granted and neither should we presume to understand the adversary without first seeking to understand ourselves. Contemplating interaction with competitors and adversaries is necessarily comparative and must be predicated on an objective assessment of the Alliance as a whole and the component national parts. The deployment of NATO-allocated forces to other member nation territory creates important opportunities to increase intra-Alliance understanding, conduct training upon potential battlespace geography, and improve integration of Alliance military formations. Such deployments, however, also present opportunities for adversaries to exploit when friction inevitably occurs between deployed personnel and the host nation.

Implication – Understanding ourselves

Forces deploying into another country as part of a NATO mission cannot be insular or simply limit their interactions to military-to-military relations. Integration with the host-nation civil population is every bit as important to developing understanding of the Alliance as is the combined training meant to ensure military readiness. There must be an emphasis on “issues identified” (both positive and negative) in post-deployment reporting at the national and Alliance level so that respective staffs can consider how these might highlight national and Alliance strengths and vulnerabilities as part of net assessment activities.

3.2.1.2 Systematic Analysis of Military Exercises

Deduction

It is common practice for Russia, NATO, and many military powers to use military exercises both to test readiness and to signal various messages to competitors and adversaries. Depending on the effect sought, it follows that some exercises will be conducted in secret or covertly and others will be overt. Most large-scale exercises combine both functions. A nation must have the ability to exercise without revealing its defence activities. Russia has a long-standing practice of combining military exercises with other instruments of power, specifically political and informational. Considered together with the timing of previous exercises with respect to explicit aggressive military activities, this suggests a rhythm that can be analyzed as part of the search for indications and warnings of Russian hostile intentions.

Implication – Understanding the other

The synchronization of military exercises with the application of other Russian instruments of power helps to link its behavior (means) to stratagems (ways). NATO benefits from its members’ and partners’ diverse strategic cultures, which shape their distinct experiences and knowledge of Russia and Russian behavior.

This breadth of perspective creates a greatly enhanced ability to understand the adversary in a way not available to a relatively isolated Russia which is more prone to the development of an unchallenged world view. Military planning at all levels must actively seek to account for differing perspectives in developing the contested advice required for rigorous decision making.

Implication – Understanding ourselves

Large NATO exercises will continue to signal Alliance readiness, resolve, and cohesion. However, given Russian proclivity to use all instruments of power as a response to what are perceived (or feigned to be) provocative actions, NATO planners will do well to consider potential second and third order effects of NATO exercises on countries and regions neighboring the Alliance. Exercise design and execution should account for the assessment of the changing operating environment (Allies, Partners, potential adversaries).

This flexibility is necessary to fully account for emerging risks and opportunities.

3.2.1.3 Spirituality and Religion

Deduction

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) has actively supported Russian government’s intent and actions before and throughout the war against Ukraine. The ROC does this by supporting propaganda narratives and by attempting to provide theological justification and blessing to Russian aggression. In addition, the ROC has contributed to Russian hybrid activities in other countries and territories. Similar minded Russian-oriented autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Churches have also directly or indirectly supported Russian political goals.

Implication – Understanding the other

Assessments of the operating environment must take into account the spiritual tendencies of the

populations amongst which military operations take place, the relationship of religious and spiritual organizations to political authorities, the historical context of those relationships in the strategic and political culture of a given population. We must not allow bias related to Western conceptions of church-state relations and assumptions on rates of religiosity cloud judgment on the spirituality of humans or specific populations.

3.2.1.4 Religious Organizations and Politics

Deduction

The ROC is not simply a proxy of the Russian government as it continues to play a significant political role that has been historically typical for many Eastern Orthodox Churches. In contrast to the more expected separation of church and state typical in Western European and North American countries, Eastern Orthodoxy has tended toward cultures of adaptability or symphony (Byzantine tradition) in which the political and religious aspects of society are intertwined. In this tradition, the church plays a political role of greater or lesser degree in some societies, countries, and territories.

Implication – Understanding the other

We must not underestimate the role of religious organizations in the day-to-day life of a population and the historical political role played by those organizations in a polity. Even when assessments of religiosity suggest a decline in adherence to formal religious practice, we should be wary of assuming that this correlates to declining perceptions of legitimacy accorded to religious authorities. This may particularly be the case when a population perceives insecurity or direct threats to national or societal stability.

3.2.2 Policy

3.2.2.1 National Interests, Alliances, and Partners

Deduction

From the implementation of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, through to the full Russian invasion in February 2022, Ukraine has, at times, been frustrated by a perceived lack of consistency in Western (e.g., EU, NATO, US) attention, policy, and support. Ukraine’s experience starkly illustrates the historical truism that national interests will always take precedence over collective interests (bi-lateral or otherwise). Great and regional powers will act as they must and alliances and political collectives will always have weaknesses associated with process and the degree of consensus on any given matter.

Implication – National policy and Alliance cohesion

Prudence dictates that the national policies of one country always consider the potential for the national interests of other countries to override any shared or collective interests. To mitigate surprise, policy generated through scenario-based contingency planning should consider the potential that agreed support will, at times, be challenged by competing interests.

3.2.2.2 Reducing Coercive Options: Limiting Dependence

Deduction

Historically, Ukraine’s economy has been weighted towards trade with Russia. This created options for Russian non-military coercion and consequent escalatory control by allowing Russia to leverage economic means for malign purposes. Over the long term, Ukraine may struggle to reduce historical trade patterns with Russia. However, doing so is required to reduce the potential for Russia to coerce Ukraine.

Implication – Reducing economic vulnerabilities

It is unlikely that the current phase (late 2022 ‒ early 2023) of the Russian war in Ukraine will result in a favorable military outcome for the aggressor. However, a strategic advantage for Russia will result if Ukraine continues, on balance, to be dependent upon Russia in economic relations. Ukraine must be able to demonstrate what is required for them to begin, and sustain, the realignment that will reduce the potential for Russia to apply economic coercion in the post-war years.

3.2.2.3 Formulating Legal Frameworks

Deduction

Legal and policy frameworks that include clear, measurable objectives are vital to a coherent approach to capability development. Failure to identify legal and policy gaps may inhibit either capability development or the nation’s ability to employ the completed capability.

NATO Implication – Review of laws

Actors engaged in capability development must be trained and educated to identify legal and policy gaps.

Stakeholders should incorporate, within the capability development process, a deliberate method for reviewing and revising laws and policies. This process is especially important in the counter hybrid warfare realm, where capabilities are often introduced to the national defence and security architecture for

the first time.

Deduction

Since 2014 Ukraine has continually developed and revised laws and policies to support unforeseen defence and security requirements. The revised laws and policies conform to accepted European Union and NATO norms as applicable. These actions have fallen broadly into three categories:

- Construct and clarify legal boundaries that mitigate the effects of Russian attempts to legitimize its aggression by misrepresenting international laws and customs.

- Create hybrid defence structures that integrate capabilities from a multitude of governmental and non-governmental organizations.

- Protect citizens’ rights within the context of territorial defence.

Ukraine Implication – Authorities, responsibilities, accountabilities

Ukraine’s capacity to counter hybrid threats will continue to rely heavily on the ability to rapidly adapt authorities, responsibilities and accountabilities that enable the integration of military and non-military capabilities. Accordingly, given the depth of unique experience Ukraine has amassed in this area, a comprehensive assessment of legislative and policy-related practices is warranted. The assessment’s aim would be to institutionalize best practices. To be fully effective, the assessment would need to account for domestic as well as international mechanisms and produce solutions that are compatible with Euro-Atlantic integration.

NATO Implication – Authorities, responsibilities, accountabilities

NATO must learn from Ukraine. The Alliance should seek Ukrainian assistance in conducting a detailed analysis of lessons relating to authorities, responsibilities and accountabilities in the context of countering hybrid threats. The results should be tailored to immediately inform NATO Bi-SC planning, training and education.13

NATO Implication – Legal and policy cohesion

Collective defence is predicated on Alliance members possessing relevant and adaptive legal and policy frameworks. In order to increase legal and policy coherence across the Alliance, NATO should create a standing platform through which Allied and Partner subject matter experts can collaboratively review laws, policies and legal practices relevant to countering hybrid threats.

NATO Implication – Adapting legal frameworks

Ukraine has had to adapt the legal framework for guiding force employment for domestic and international operations. NATO member nations should take into consideration that they may have to do likewise and have draft contingency legislative amendments that would enable rapid adaptation.

3.2.2.4 NATO Capability and Capacity Building

Deduction

Unity of effort is difficult to achieve but critical when multiple international actors assist a partner’s capability development efforts. Each actor, as well as the partner, will likely have divergent interests, dissimilar capacity building capabilities and disparate resources. Absent a mandated unified structure, the community can only achieve coherence through voluntary cooperation.

Implication – Unity of effort (I)

When engaged in capacity building, NATO and individual Allies should continuously seek to unify efforts.

Agreements between NATO and the partner, which by definition have been approved by all Allies, make an excellent starting point. After identifying the intersection for the greatest number of interests possible, stakeholders should be encouraged to establish a standing organizational structure with linkages to all other critical nodes within the capability development network. Finally, all involved should operate from a single plan that is overseen, not by the supporting element but by the supported partner.

Deduction

NATO’s capacity building experience in Ukraine exposes the lack of a common methodology, not only among Allies but within NATO as a body. Rather than a whole-of-government and whole-of-society undertaking, the defence and security community tends to view capacity building through a tactical military lens. In this context, NATO presents mobile training teams, exercise and academic courses as the primary tools for building capacity. The NSHQ’S Building SOF Capability Handbook and course and the steps NATO is taking within the framework of NATO 2030 are aimed in the right direction. However, these measures lack the immediacy required to reduce redundancy and increase effectiveness in areas where capacity building is ongoing.

Implication – Unity of effort (II)

The Alliance would benefit from a comprehensive approach to capacity building. An authoritative organization within NATO’s civilian leadership structure should be charged with publishing a handbook to guide NATO-supported capacity building efforts. The handbook would aim to establish a common frame of reference for those operating from the national through unit level. Courses related to capacity building that are currently taught at NATO Special Operations University, NATO Security Force Assistance Centre of Excellence and other academic institutions across the Alliance should be aligned with the principles and practices outlined in the handbook.

3.2.2.5 NATO-UN Partnerships

Deduction

NATO and the UN have a valuable partnership in facilitating peace operations. Nevertheless, the exchange of information and expertise with the UN and NATO support to peace operations remains important.

However, in the context of the conflict in Ukraine, NATO is not perceived as a neutral party by Russia but the UN must be seen as non-aligned. As a result, NATO support to UN operations in post-combat phases may face difficulties.

Implication – Reassessing partnerships

NATO may have to reassess existing NATO-UN partnership agreements in order to reinforce NATO-UN cooperation. NATO may assist in contingency planning for the provision of UN assistance when faced with Russian opposition within the UN and provide logistical support to humanitarian assistance. Other areas of consideration include humanitarian de-mining, capacity building, Civil-Military Co-Operation (CIMIC), and post-combat reconstruction.

3.2.2.6 Article 5, Hybrid Methods, and Alliance Cohesion

Deduction

Article 5 is the cornerstone upon which NATO will ultimately succeed or fail. However, invocation of Article 5 requires consensus and agreement that the actions of an adversary have met an agreed-upon standard that is necessarily contextually derived. Malicious activity meant to challenge, but not cross, opaque national and Alliance “red lines” is a common feature of Russian behavior.

Implication – Alliance cohesion and Article 5

The Alliance must assume that Russia will continue to conduct covert and overt activities using all instruments of power in a manner that is meant to undermine the cohesion of the Alliance without triggering Article 5. No easy solution exists to this problem. Whilst having agreed to NATO’s Core Tasks, Allies have different perceptions of what those tasks entail. Some see NATO at the core of both collective security and collective defence, while others see collective security as a broader network of activity of which NATO is a component. This contributes to differing perceptions of what constitutes an “attack” sufficient to justify invocation of Article 5.

Implication – Relationships between the instruments of power

Russian hybrid activity has been shown, at times, to be a precursor to broader, more obvious aggression. The Military Instrument of Power (MIOP) represented by NATO must be closely tied to other instruments of power at the national and supranational level. This is necessary to ensure awareness and preparation of appropriate options to prevent Russian attempts to shape the operating environment in its favor and mitigate Russian stratagems.

3.2.2.7 Indications, Warnings, and Article 4

Deduction

NATO, its member nations, and its partners must ensure security and defence organizations and processes are aligned to provide timely indications and warning of possible or impending adversary action. Those indications and warnings must also be collated to ensure an integrated common operational picture.

Implication – Integrated common operating picture

An integrated common operating picture that is comprised of indications and warnings from Allies and Partners can be used to trigger timely political-strategic and military-strategic discussion that is necessary to mitigate or counter adversary action or, in the worst case, create the conditions for well-grounded consideration of whether an Article 5 invocation is warranted.

3.2.2.8 Finding Common Ground

Deduction

The mandate and activities of Kosovo Force (KFOR) represents an example of Alliance policy or actions coinciding with adversary policy or operational goals in a manner complementary to both sides. While working to achieve different ends, such examples allow for NATO to continue having a presence in a potentially volatile region.

Implication – Synchronicity

While opportunities for such synchronicity may be few and fleeting, Allies and Partners should be prepared to identify situations where this can open doors for dialogue or mitigate against unintended escalation. A net assessment mindset will help conceive of potential opportunities for constructive interaction with adversaries and contribute to identification of common ground.

3.2.3 The Military Instrument of Power

3.2.3.1 Adapting Force Structure

Deduction

In the aftermath of the 2014 phase of the illegal Russian aggression, the Ukrainian Armed Forces recognized that their military effectiveness was predicated on the ability to adapt force structures to integrate national capabilities. This enabled more effective counter hybrid approaches.

Ukraine Implication – Identify reforms

Using the NATO defence capability framework, identify the reforms necessary to institutionalize best practices for rapidly forming cross-functional military units for immediate employment against hybrid threats.14

3.2.3.2 Situational Picture and Awareness

Deduction

One of the key decisions in the success of the Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO) made by Ukraine was to establish a joint situation room participated by all necessary agencies and authorities. The Main Situation Center of Ukraine made it possible to create a common recognized situation picture and to generate accurate situational awareness in order to make the necessary decisions to counter-act against actions of Hybrid Warfare.

Implication – Comprehensive defence

Collective defence assumes NATO member nations have comprehensive national security and defence architectures. Any gaps at the national level undermine the security and defence of the Alliance. National level structures and processes must be tailored to enable situational awareness appropriate to the character of hybrid threats. Such efforts should be properly networked and able to integrate with Alliance structures and processes.

3.2.3.3 Wartime Military Effectiveness

Deduction

The Ukrainian experience of learning, adapting, and innovating during wartime conditions is an exemplar for how military forces must rapidly embrace change in a manner that produces tangible results. Since 2014, Ukraine has taken dramatic whole-of-nation steps that manifest in maximized combat power.

Implication – Learning and adaptation

NATO should seek to learn as much as possible from the Ukrainian experience and support Ukraine in the continual effort to sustain learning over time.

3.2.3.4 NATO Operational Planning: Long-Term Threat

Deduction

The Russian approach to hybrid activities has always relied upon the existence of sizable military forces.

Any cessation of major combat operations in Ukraine will not fundamentally change this. However, as a result of combat losses in Ukraine, it will likely take Russia a number of years to reconstitute its combat power. During this time, Russian use of non-military means will likely take on a more prominent role in their efforts to coerce other states and organizations.

Implication – Russia as a long-term threat

Regardless of the outcome of the conflict in Ukraine, Russian determination in pursuit of national interests should not be underestimated. Both Ukraine and NATO should prepare for a protracted challenging relationship with a hostile Russia. In addition, Ukraine will require assistance with the rapid reconstitution of its military forces. It may prove challenging to sustain Alliance agreement on the threat posed by Russia.

NATO must ensure that national military forces are comprised of relevant capabilities that are held at appropriate readiness in order to provide flexible response options.

3.2.3.5 Laws of War

Deduction

The actions and behaviors of Russian forces and Russian-backed proxies in the war against Ukraine have not conformed to international and humanitarian law or the laws of armed conflict. In addition, the character of the war in Ukraine as perpetrated by Russia carries with it a heightened level of brutality.

Implication – Mental resilience

The dehumanizing effects of warfare as perpetrated by Russia in Ukraine demand NATO pays greater attention to the mental resilience of both the individual and the group. This may include learning from Ukraine’s current experience, supporting them with the near and longer-term psychological effects of the war, and the relevance of current educational processes that seek to prepare personnel.

3.2.3.6 Integration of Military and Non-Military Capabilities

Deduction

The integration of military and non-military capabilities is perhaps one of the most difficult aspects of countering hybrid threats. Ukraine expended great effort since 2014 exploring and analyzing various concepts and models to address shortcomings identified during this time. Ukraine has demonstrated that they adapted sufficiently in response to the existing threat. However, it should be noted that bureaucratic practices function differently when not under the duress imposed by wartime conditions. NATO can learn from Ukraine’s wartime experiences.

Implication – Integration and absorbing the lessons

Institutionalization of best practice regarding the integration of military and non-military capabilities will require the deliberate construction of agile and interoperable concepts and models. These must address the integration of decision-making processes and cycles, the interoperability of platforms and systems, and include a continuing program of testing and experimentation that challenges those concepts and models. These must be reflective of functional expertise, the lines of authority that characterize organizational mandates and culture and place a high value on simplicity for the purposes of clarity and agility in application.

3.2.3.7 Ukraine’s Information Security: Mental Resilience

Deduction

Ukraine’s approach to Information Security (InfoSec) includes both the physical/technical dimension as well as the cognitive. The latter focuses on means to strengthen cognitive resilience and/or mitigate subversive activity, especially in regard to own forces. This approach is reflective of the main elements informing the development of the NATO cognitive warfare concept.

Implication – Mental health and morale

Approaches to information security must be tailored to the context. However, Ukraine’s emphasis on cognitive resilience is a very important factor to consider and links to a number of other implications discussed herein. Ukraine will be able to teach NATO many lessons but, perhaps, the most significant will be in ensuring the cognitive resilience of forces. NATO and Ukraine should collaborate in the post-combat period to begin to understand the measures taken by them to sustain the mental health, mental resilience, and morale of their personnel, formations, and decision-makers.

3.2.3.8 Strategic Communications and Internal Resilience

Deduction

Ukraine’s approach to strategic communications seeks to ensure that service members maintain complete awareness of the mission and evolving situation at all levels. The warfighters are able to discern enemy disinformation while reinforcing the official strategic communications message through their actions. To further contribute to resilience in the face of disinformation, the approach also affords consideration to the individual and unit morale.

Implication – Building trust

As Ukraine continues to refine the internal communications element of strategic communications, it is important to continue to implement measures that increase trust throughout the chain of command. The goal should be to eliminate dependence on any actors who are not subordinate to the unit commanders’ direct authority. Under the objective model, any specialists or subject matter experts provided by a higher headquarters would be officially attached to the supported command and answer directly to that commander.

3.2.3.9 CIMIC in a National/Allied Context

Deduction

Historically, CIMIC has proven to be a flexible doctrinal concept, adaptable to specific conditions. Ukraine refined its approach to CIMIC by balancing NATO standards with the specific requirements dictated by the reality of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. While Ukraine has institutionalized CIMIC as a doctrinal concept, this flexibility of application will be critical in the reconstruction and reconstitution phases.

Implication – Societal resilience

NATO CIMIC must be prepared to adapt current doctrine, training, and education in light of lessons identified resulting from the Ukrainian experience. In particular, this effort should place emphasis on understanding the requirements necessary to support NATO member national resilience when faced with hybrid aggression. It may be useful to revisit some of the lessons learned from the West-Balkan Six (WB6) in the 1990s, early 2000s, and the ongoing KFOR mission.

3.2.3.10 Exercise Analysis: Frontstage (Public), Backstage (Veiled) and Mystification

Deduction

Russia’s public pronouncements regarding military exercises are meant to create legitimacy by both communicating to broader public and official audiences (e.g., compliance with OSCE 1999 Vienna Document).

Russia uses such “frontstage” acting as a means of obfuscating “backstage,” or veiled, undeclared actions during military exercises as part of coordinated information campaigns. Backstage acting can be analyzed from the notion of “mystification,” in which Russia attempts to influence the perception and interpretation of its veiled as well as its public actions and intentions. In contemplating Red-Blue interactions, “mystification” has the potential to create uncertainty by reinforcing false assumptions and conclusions. This phenomenon exploits actors’ susceptibility to disinformation created by a constant need of knowing.

Implication – Read between the lines

The way Russia attempts to build legitimacy for its actions is an important part of the stratagems it pursues.

Public pronouncements by Russia must not be dismissed. Rather, they should be studied for indications of possible “backstage” acting. It should be expected that other adversaries will use similar means whenever possible.

Implication – Exercises and campaign design

The Alliance can apply the principles of Frontstage-Backstage acting to enhance exercise planning.

In addition, NATO should seek to incorporate exercises as an integral part of outward-focused, enduring campaign design in addition to testing readiness and conducting gap analysis.

Implication – Intelligence framework

Frontstage-backstage can serve as a useful framework for intelligence analysts to deduce Russian messages and intentions in the run up to and their execution of military exercises. This framework can be added to intelligence methods to assist in the analysis of adversary military exercises in relation to other activities within the broader operational environment.

3.2.3.11 Military Strategies to Handle Russian Backstage and Frontstage Acting

Deduction

The combination of frontstage and backstage acting makes it possible for Russia to calibrate different means to reach strategic goals. Frontstage acting captures the interest of the audience and presents images and fragments of Russian actions. Backstage acting enables sensitive military planning, intelligence collection, and discrete and covert operational action. Backstage acting can be analyzed from the notion of “mystification,” in which Russian secret actions increase the attentiveness and focus of western audiences on the meaning and portent of Russian behavior. This phenomenon may construct a western susceptibility and a constant need of knowing, which might be misused by Russia in disinformation operations.

Implication – Unintended effects

NATO must consider these challenges in the military planning processes and implement military strategies with the ability to act both with temporal variations and with considerations of potential consequences.

As such, consequences include those that affect not only NATO as an alliance but also individual members (i.e., neighboring countries to Russia or nations vulnerable to Russian influence). Alliance planning must, as a first principle, consider the impact of plans and actions on Alliance cohesion, with an eye to removing vulnerabilities that can be exploited by competitors and adversaries.

3.2.3.12 The Application of the Military Instrument of Power (MIOP)

Deduction

The MIOP provides decision-makers with an extensive array of capabilities not possessed by the organizational structures comprising other instruments of national or Alliance power. Most certainly, the mandate to wage war when directed is unique to the MIOP. Recourse to the MIOP will affect Red, Blue, and Green perceptions (adversary, allied, partners and others), consequent deterrence calculations, and the information environment overall. Alternatives to the NATO MIOP may be preferable. For example, situations may be better addressed using non-military tools and resources available to political leaders.

Implication: Use of the MIOP

Particularly in the current and anticipated future operating environment, careful consideration must be given to whether military forces and the capabilities they possess are the best suited to the problem at hand.

Military leaders and personnel often exhibit a ‘can-do’ attitude which is both admirable and necessary for military effectiveness. However, representatives of the MIOP must voice their professional assessment and judgment regarding the appropriateness and potential negative consequences of the use of military capabilities for a given task.

3.2.3.13 MIOP Backstopping Hybrid Activity

Deduction

Military forces are often employed as a force-in-being to represent a deterrent that can limit target response options to non-military (“hybrid”) activity. For example, an adversary can affect “red line” calculations of its target when they possess credible military capabilities, the use of which may come into play if a response is made.

Implication – Force posture

The posturing of Alliance forces to signal collective resolve should continue. The careful use of force posture most certainly affects Russian calculations on the use of non-military methods, even if that is not always perceived to be the case.

3.2.4 Homeland

3.2.4.1 Electronic Warfare: Prevention and Protection

Deduction

Electronic Warfare (EW) capabilities remain an important component of Russian conception of intelligence collection, warfare and warfighting. Many, if not most, state and non-state threat actors consider disruption of C4ISR and civilian networks as critical elements in conflict, warfare, and warfighting. Even minor transnational criminal organizations will attempt to disrupt networks for criminal purposes.

Implication – EW shielding

Shielding from adversary EW capabilities is increasingly important, not only for security and defence installations and equipment but for civilian infrastructure and communications as well. EW shielding must be seen as a mandatory peacetime requirement.

3.2.4.2 Homeland Defence is the Bedrock of Alliance Cohesion

Deduction

Russia attempts to tailor the application of its instruments of power to the specific national context of its targets. When considering the Euro-Atlantic theatre, the targeting of national level vulnerabilities often has a primary or secondary goal of creating or exploiting existing friction points in intra-Alliance relations.

Implication – National political-strategic arrangements

Coherent, resilient national security and defence architectures (conceptual approach, legal foundations, organization, and process) are the bedrock of Alliance cohesion and military effectiveness. An enemy will seek to exploit tactical or operational weak points in the battlespace. Gaps at the national (political-strategic) level and within NATO will be exploited by adversaries to the ultimate detriment of collective defence.

Deduction

Inadequacies in Ukrainian legal frameworks hampered the ability of the security and defence sector (organizations) to coherently respond to Russian aggression beginning in 2014. Significant modernization of security and defence legislation continued through to the February 2022 Russian offensives. Ukraine’s continuing ability to defend itself is predicated on the implementation of revised policy and legislation.

Implication – National legal frameworks

Many NATO member and partner nations have sought to revise legal frameworks to address consistently evolving issues such as cyber operations, information security, and other similar contemporary topics.

National level legal frameworks must enable comprehensive (whole-of-society) security and defence of the nation. It will always be necessary for NATO planners to reconcile differences in national legal frameworks but this necessary work will be unduly complicated if gaps in national frameworks exist.

Deduction

Critical infrastructure tends to be defined with slight differences at the national and multi-national level.

Adversaries and malicious actors of all forms seek to target the assets that comprise critical infrastructure as a means to achieve desired ends.

Implication – National critical infrastructure

Allies and Partners can help ensure collective defence preparations by identifying, in detail, the national level public and private assets that comprise national critical infrastructure. Such preparations must include hierarchical considerations that allow for prioritization of what must be defended, identification of vulnerabilities, and plans for the mitigation of those vulnerabilities.

Deduction

It is not unknown for Russia to employ sabotage against critical infrastructure and other sensitive targets.

Implication – Sabotage

It is important for national security and defence preparations to assess potential vulnerabilities in context of sabotage. Allies and Partners should expect Russia to pre-position caches of critical equipment typically required to conduct sabotage.

3.2.4.3 National Homeland Defence Concepts

Deduction

The varying strategic cultures of Allies and Partners affect the formal and informal conceptions of national security and defence at the national level. Portions of national legal frameworks, policy options and actions that might be appropriate and permissible in one country may not be seen as such in another.

Implication – Reconciling concepts

The effectiveness of Alliance political and military-strategic planning is predicated upon constant effort to understand Allies and Partners and must not be taken for granted, particularly as the expansion of the Alliance is contemplated once again. In seeking to understand ourselves, it is important for each Ally and Partner to articulate the historical and contemporary basis for their conception of homeland defence.

In addition, it is the responsibility of each nation to build understanding of the perspectives of others.

3.2.4.4 Business and Investment – The Economic Instrument of Power

Deduction

Russia frequently uses private (vice state owned) business and investment for several purposes:

- Control interests in critical national level industries;

- Influence political decisions (at all levels of government);

- Purchase real property that is near sensitive national infrastructure;

- Purchase real property that is geographically situated in such a manner that it could be used to gain

- military advantage; and

- Influence the development or ownership of energy infrastructure to shape energy flows to advantage.

Implication – Foreign direct investment

A balance between national security and economic interests must be struck. Diligence must be applied to uncover true ownership of companies, the origins of capital flows being used in foreign direct investment, and to uncover situations where adversary governments may be inappropriately influencing ostensible business decisions to gain advantage in security and defence affairs.

Implication – Foreign ownership of real property

Direct and indirect foreign ownership and development of real property near critical infrastructure and sensitive security and defence installations must continue to be carefully scrutinized.

3.2.4.5 Influence on Non-Governmental Organizations

Deduction

Russia has an established practice of manipulating non-governmental organizations in the pursuit of strategic goals in ways that do not contravene national legal frameworks. Russia continues this tradition in various ways including at the local level to influence the development of energy infrastructure and backing youth groups that are used to influence the perceptions of adolescents in ways favorable to Russian interests. Such activities are not limited to the local level, however, as Russia has also sought to influence and control domestic and multi-national NGOs.

Implication – Transparency and legitimacy

Liberal democratic states must engage in continuous information campaigns to expose inappropriate influence or relationships between adversary governments and NGOs.

3.2.4.6 Homeland Defence: Readiness

Deduction

Ukraine’s experience in 2014 and 2022 reinforces the importance of high readiness homeland security and defence forces and the interagency connections required to facilitate comprehensive homeland defence.

Implication – Professional development and exercises

Combined, interagency professional development and exercises are necessary to establish and maintain national security and defence readiness. These activities are required regardless of the perceived efficiency of processes and technical arrangements meant to facilitate homeland defence.

Implication – Planning

Realistic, iterative, threat-based contingency planning is necessary to facilitate combined, interagency homeland defence exercises. Long-term, intelligence-driven, threat-informed military and non-military strategic planning is required for the development of combined, future-oriented advice to political authorities. In addition, this helps to ensure the relevance of the national security and defence architecture to expected future conditions.

Implication – Indications and warning: Domain awareness

Comprehensive and integrated domain awareness is necessary for homeland and collective defence.

Particular attention should be paid to cyber and maritime domain (particularly inshore maritime) awareness, as Russia regularly exploits these areas.

3.2.5 Information Environment

3.2.5.1 Strategic Communication in Transition: ‘Total War’ to ‘Post-(Major) Conflict’

Deduction

In the current context, Ukrainian wartime strategic communications are relatively straightforward – there is a clear aggressor and a defender and there is little contestation of core messages within strategic communications. Ukrainian strategic communications must be prepared for a shift in the information environment that will see a rise of internal challenging of political messaging characteristic of robust democratic systems. Ukrainian strategic communications will need to consolidate Ukrainian success in a manner that supports sustaining international attention on Ukraine’s needs as they begin reconstruction and reconstitution.

Implication – STRATCOM doctrinal alignment

Building upon the 2015 Ukraine-NATO strategic communications road map, Ukraine could consider applying the new AJP-10 Allied Joint Publication on Strategic Communication. This document could serve as a tool to guide Ukraine as it transitions from wartime to post-combat phases. Applying AJP-10 will also help achieve the goal of doctrinal alignment with NATO.

Implication – Countering post-war malign messaging

Russia will attempt to undermine Ukraine indirectly through renewed emphasis on global strategic communications. In some cases, Ukraine and its partners will have to invest further in the manner by which strategic communications are conducted. Greater emphasis should be placed on the assessment of effectiveness of these efforts in order to successfully counter Russian messaging.

3.2.5.2 NATO Strategic Communications and Shared Understandings

Deduction

How close a country is to a military threat fundamentally alters the likelihood with which states consider their requirements for defence. This includes the extent to which NATO is factored into their defence.

Member nations who are further removed from likely conflict zones may struggle to understand the perspectives of those most likely to have to invoke Article 5. This creates opportunities which may be exploitable by Russia or other adversaries.

Implication – Shared understanding of threats

Common understandings and coherent approaches to countering hybrid activities rely upon shared understandings of threats. NATO strategic communications have an important role to play in supporting the development of shared understandings across the Alliance and this point must be carefully considered during the routine revision of doctrine and consequent application to headquarters functions and processes.

3.2.5.3 Countering Russian Rhetoric

Deduction

Russian strategic level “frontstage” acting is performed by government authorities, including the Ministry of Defence, special services, Russian Orthodox Church, and Russian media personalities and outlets. Political speeches and informational activities spread both through Russian Ministry of Defence (MoD) and media.

Common themes highlighted by Russia include:

- Construction of NATO as a threat to Russia.

- Presentation of Russia as an agent of peace and stability.

- Confronting strategies in the political and information dimension.

- Accusations against opponents (for example, Russophobia).

- “Play the relation card” (e.g., exaggeration of a relationship with another nation).

Implication – Developing joint policies and doctrinal approaches

NATO and its partners must continue to develop joint policies and doctrinal approaches suitable to countering the consistent themes of Russian rhetoric, especially as those relate to attempts to create friction between the Alliance and partner nations. NATO aspirants, such as Sweden and other partners must study and absorb issues identified and lessons learned from Alliance strategic communications to help support the development of strategies and reduce malign influence from Russia. NATO may also learn from external experience and knowledge concerning Russia, such as from NATO partners.

3.2.5.4 Focus on the Effect

Deduction

The Russian government separates activities in the information environment into two conceptual categories, that of a) information-technical (the technical means of intervention), and b) information-psychological (the psychological effect). These categories are interdependent and complementary. Whilst the technical effects may be most obvious in the first instance, the psycho-social effect generated in a target audience are often less easily identified.